Under the Western Pedestal

A sneak preview of Modern Art History: Women and POC

Written by instructor Liesa Lietzke

Left: Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller. Catalogue image of Ethiopia (later known as Ethiopia Awakening), 1921. Cast Bronze. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

Right: Funerary Figurine of King Pinudjem I, ca. 1025-1007B.C.E. Faience, 4 1/8 x W. at elbows 1 7/16 in. (10.4 x 3.7cm). Brooklyn Museum. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

Image description: On the left is a black and white catalogue photograph of Meta Warrick Fuller’s sculpture, Ethiopia (later known as Ethiopia Awakening). It’s a sculpture of a feminine figure that references the aesthetics of ancient Egyptian art. The left hand is turned outward at the wrist in a playful gesture, suggesting a flick of motion. On the right is a polished blue stone Egyptian funerary sculpture of of King Pinudjem I, inscribed with black hieroglyphics. The figure’s arms are crossed over his chest, and he looks solid and unmoving.

Ethiopia Awakening

Ethiopia Awakening became iconic during the Harlem Renaissance. Early 20th-century American artist Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller references not only Ethiopia (in the title) but Ancient Egyptian art in this particular sculpture, connecting the 1920s present and her Black American identity with an African heritage: ironically, this is the same African heritage that Western Art claims as its origin.

San Francisco’s art museums and universities stand on Ohlone land; New York’s on Lenape land. Here and everywhere between, white European-Americans have constructed a narrative of the Western World. In it, your basic college art history offerings for non-majors are predictably Western Art History, otherwise known as Art History; thus, whether you take a four-semester sequence of these classes or just one whirlwind tour, you will primarily be exposed to European and American art. Yet where does this timeline begin? And, a more complex question: what do you see, when you peek under the pedestal of Western art?

Boundaries (in blue) of the “Western World” (based on Samuel P. Huntington's 1996 book Clash of Civilizations.) Image: Wikipedia.

Image description: A world map showing color-coding in dark blue, light blue, and gray, that defines the boundaries of the Western World, as imagined by political scientist Samuel P. Huntington.

In the typical undergraduate sequence (after Prehistoric art, which is found all over the world but mostly discussed in terms of Europe) comes Ancient art. The Ancient period begins once we’ve entered into historic times (marked by the use of written language), and it begins in Africa and the Middle East (“Middle” as seen from the West). Egyptian and Mesopotamian artworks are recognized as central even to Western art history--although they obviously fall outside the boundaries of the West. What counts as the Western World? According to Harvard political scientist Samuel P. Huntington, it’s Europe, America, and some of their colonies. But the timeline of Western Art is often presented beginning with Ancient civilizations of Africa (usually exclusively Egypt) and the Middle East (Contemporary Iraq, Iran, Kuwait). Once Ancient Greek culture emerges, Western art history is smitten. Finally, a white, male-dominated culture, which can be forever after considered the pinnacle of artistic excellence! Thus latched on to white accomplishments, the Western narrative largely dumps Black and brown people, and never looks back--until the Harlem Renaissance. This claim of African and Middle Eastern art in the Western art historical timeline could be seen as a kind of large-scale act of cultural appropriation, especially when followed by the conspicuous absence of recognition of artists from these regions--or any Black and brown artist--until the 20th century.

In 1921, a time when the Harlem Renaissance movement was still nascent, W. E. B. Du Bois asked Black American artist Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller if she would make a submission to the New York exhibition America's Making, which centered the contributions of immigrants to American culture. In response to Du Bois’ request, Fuller created Ethiopia.

Despite its title, the sculpture is a woman standing in the Egyptian funerary posture, with her lower body swathed like a mummy. The wrapping is partially undone and held in the figure’s hand which crosses her chest. Even 1920s Americans associated the gesture of both hands grossing the chest (likewise the headdress) with Egyptian sarcophagi, mummies and other funerary art such as the figurine shown above. But in this case, the other hand is at her side, with a playful gesture that emphasizes the theme of awakening: she is coming alive, not bound, but free; not in Ancient Egypt, but in the present moment. As Renee Ater writes in “Re-Making Race and History: The Sculpture of Meta Warrick Fuller, “Contemporary scholars interpret Ethiopia Awakening as a Pan-Africanist work, symbolizing a reawakening of African Diaspora identity. The statue, celebrated for ushering in the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, seemed to mark a new dawn of black intellectual life and creative production” (Ater 2011).

Mary Turner, another work by Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller. Painted plaster, 1919.

Image description: A sculpture of a woman dressed in a long, sleeved dress, colored a bronze tone. The figure’s gaze is downward, and her arms are cradled near her stomach. The dress appears to transform into expressively carved hands and faces that gaze upwards towards the figure.

Fuller didn’t begin her practice with themes of collective awakening. After attending Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art on a scholarship won on the merits of her high school artwork, Fuller established herself professionally in a productive sojourn in Paris, where she continued her education and exhibited work at the Paris Salon and other prestigious venues. Her work was influenced by the Symbolist movement and often showed dark and haunting scenes. Later, after returning to America, she encountered the expectation that she speak to the Black experience and identity in her work (Davidson 2020). Upon marrying, she also found herself pressured to assume a housewife role. She rented herself a studio yet hid this fact, at first, from her husband, to avoid his objections. Later, she built a studio at home, also against her husband’s opposition. Before--and sometimes after--the second wave of feminism in the 1970s, this lack of partner support was an unfortunately common experience for artists, as it was for women in other professions. Happily for Fuller, she found support as an artist among Black scholars and influencers of the New Negro movement and the Harlem Renaissance.

W. E. B. Du Bois was a family friend and encouraged and supported Fuller in her work in many ways, including his invitation to America's Making and beyond. Philosopher and chronicler of the Harlem Renaissance Alain Locke later noted her in his book The New Negro: An Interpretation (1925), a movement-defining anthology of literature, music and visual art which helped to crystalize the Harlem Renaissance. While not impressed by her earlier work, Locke praises Ethiopia, which he renamed Ethiopia Awakening. This re-titleing, as well as his lack of enthusiasm for her earlier work, is indicative of Locke’s interest in art that spoke to a collective Black identity. “Ethiopia Awakening...to [Locke’s] mind, revealed where race-based work could go if guided toward ‘representative group expression.’” (Davidson 2020) Other art historians ”have rightly discussed this sculpture in terms of its Pan-African ideals and the way in which the work symbolized a new radicalized Black identity at the beginning of the Harlem Renaissance…” (Ater 2003). Fuller herself might not have thought of this as the trajectory and purpose of her work, but Locke’s writing certainly established this piece as symbolic of the movement and its purpose of Black liberation.

W.E.B. Du Bois, circa 1911. Gelatin Silver Print. Collection of the National Portrait Gallery. Image: Wikipedia Commons

Image description: A black and white side-view photographic portrait of W.E.B. Du Bois, taken around 1911. Du Bois is facing left, and his gaze is slightly downward. He is softly lit and he is wearing a suit, dress shirt, and tie.

This emphasis on collective Black awakening was among the central themes of the New Negro/Harlem Renaissance movement, as is clear in some of the the major works of painters Aaron Douglas and Jacob Lawrence (as well as in Locke’s comments above). Yet this collectivism is at odds with the mythologies of Modern Western Art, which is generally more concerned with placing the individual hero on a pedestal.

The Illusion of Solidity

Mid-century Modern Western art is particularly invested in the trope of the rugged individual genius. And, when it’s time to choose a cover model for artistic success, Western culture stays true to its male-supremacist aesthetic philosophies. In the earliest Western commentaries on aesthetics, German philosophers Friedrich Schiller and Immanuel Kant characterize creativity as a male impulse, within which the only female role is as muse and subject. Whiteness is so integral to this position that it doesn’t even bear mentioning by these philosophers. That was 18th century Germany, but in the American mid-20th (and arguably still into the 21st), we find that this trope has persisted, making male--particularly white--talent more readily recognized, offered opportunities, and held up as valuable.

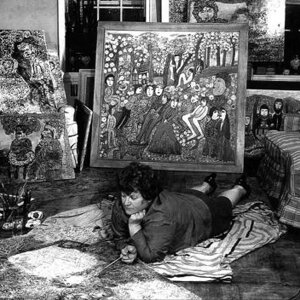

Janet Sobel in her studio, date unknown. Image: Wikipedia

Image description: Janet Sobel lies on her stomach on the floor of a studio, working on a piece. Behind her, paintings lean up against the walls and windows of the studio.

In the 1940s, a New York artist created the drip technique, which became the best-known feature of Abstract Expressionism, which was then hailed as the most important movement in American art (despite coming on the heels of the Harlem Renaissance). That artist was Ukranian-American, self-taught Janet Sobel. Her 1945 painting The Illusion of Solidity shows another feature generally credited to Pollock, besides the drip technique: the all-over composition, which emphasizes the flat surface and the paint/canvas relationship, and doesn’t divide it with any illusion of separate forms in a figure/ground relationship. This was especially praised by the well-known New York critic Clement Greenberg as indicative of quintessential high Modernism. The monumental scale of his paintings, on the other hand, was inspired by the Mexican mural art of this time.

Hey, wait--what did Jackson Pollock have that Sobel didn’t? What made him the star? Besides a penis, Pollock had Greenberg, the highly influential art critic who, as I said, sang the praises of AbEx in general and Pollock in particular, leading to both the movement and the artist’s widespread exposure and popularity. These two men knew Sobel: both visited her studio. Pollock admired her work and admitted that it influenced him. He took the drip technique that Sobel was pioneering, and he ran with it--all the way to a Time Magazine feature that made him a household name.

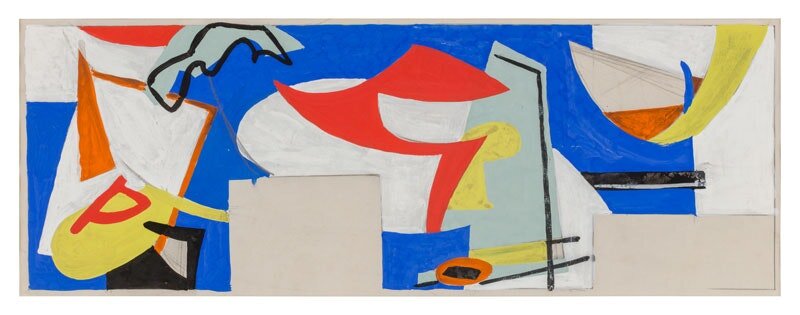

Lee Krasner. Untitled Mural Study, 1940. Gouache on paper, 17 x 22 inches. Study for a Mural Krasner did for the WPA, an American New Deal agency. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

Image Description: A long, horizontal painting by Lee Krasner. The painting is colorful, with lively, brushy geometric shapes in bright shades of blue, yellow, red, and orange, which are complemented by more neutral blocks of color such as beige, gray, white, as well as narrower black shapes and lines.

Greenberg also praised Sobel’s work, but always as secondary and inferior to Pollock’s, emphasizing derisively that Sobel was a “housewife.” That’s two full-time jobs, then? Why is that not something to be admired? Because it is a female occupation. As we saw with Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, in this era before second wave feminism, women practicing any profession were scrutinized by a culture that wanted to be sure they weren’t shirking their (unpaid) feminine duties. What a horror that would be--the world would cease to turn (to be fair, if you look at the sum total of unpaid labor even just at this time, let alone during slavery, yes, actually the world would cease to turn).

The point is, without Sobel--and without Greenberg, without the wealthy collector and patroness of the arts Peggy Guggenheim, without Pollock’s artist wife Lee Krasner who introduced him to Greenberg and other influential figures in the New York art scene, as well as tirelessly promoting his career, even over her own--would there have been a Pollock? Each had a key role in Pollock’s success. Sobel and Krasner were artists arguably at least as good as he was. Yet he stood on the pedestal, as the star of Abstract Expressionism. Pollock became not only the face of AbEx, but of American rugged individualism itself, when the CIA decided that his work was an ideal foil to Russia’s Socialist Realism (McBride 2017).

The European and Euro-American view that a white man must be the face of accomplishment requires that all other figures (however essential to that accomplishment) be hidden, to create the illusion of individuality. This repeats the claim of origin and originality which erases any other or prior, much like the Wester art historical narrative from Classical Greece onward.

Interested in learning more? Check out Liesa’s class, Modern Art History: Women and PoC!

Works Cited

Anfam, David. “How Abstract Expressionism changed modern art.” RA Magazine, a Publication of the British Royal Academy of Art, Autumn 2016. https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/article/abstract-expressionism-beyond-the-image

Ater, Renée. “Making History: Meta Warrick Fuller's ‘Ethiopia.’” American Art, Vol. 17, No. 3. (Autumn, 2003), pp. 12-31. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5acf8bf7a9e028b9d3e33f81/t/5e4af73ba78e4d69b890572a/1581971270825/rater_fuller_ethiopia.pdf

Ater, Renée. “Remaking Race and History: The Sculpture of Meta Warrick Fuller.” University of California Press. 2011. Introduction.

https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520262126/remaking-race-and-history

Davidson, Benjamin and Biddle, Pippa. “The Sculpture of Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller.” The Magazine Antiques, October 13, 2020. https://www.themagazineantiques.com/article/the-sculpture-of-meta-vaux-warrick-fuller/

Hawlin, Thea. “Five Forgotten Female Artists of Abstract Expressionism.” Another: Art and Photography, 2016. https://www.anothermag.com/art-photography/9101/the-forgotten-female-artists-of-abstract-expressionism

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, Ethiopia, 1921. The Smithsonian Museum of African-American History and Culture. https://nmaahc.si.edu/meta-vaux-warrick-fuller-ethiopia-1921

McBride, Michael R. “How Jackson Pollock and the CIA Teamed Up to Win The Cold War.” Medium, 2017 https://medium.com/@MichaelMcBride/how-jackson-pollock-and-the-cia-teamed-up-to-win-the-cold-war-6734c40f5b14

Sutherla, Claudia. “Meta Warrick Fuller (1877-1968)” Black Past, 2007 https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/fuller-meta-warrick-1877-1968/

Zalman, Sandra. "Janet Sobel: Primitive Modern and the Origins of Abstract Expressionism." Woman's Art Journal 36, no. 2 (2015): 20-29. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26430653